My beautiful mother, Shirley, passed away on 28 September, aged 83. This is – with some amendment because I am nothing if not a perfectionist when it comes to writing – the eulogy I wrote for her funeral.

Last year my Mum had the opportunity to write down her thoughts about her own mother as part of a local history project. ‘She was a great mother, I couldn’t have had better’ is what she wrote. And sitting here writing my Mum’s own eulogy, my thoughts are exactly the same. She was a truly wonderful mother, and I cannot imagine how she could have loved us any more or better than she did.

Also like her own mother, Mum was an incredibly tough and hard-working woman, who spent the majority of her life cooking meals in kitchens in hotels. Although Mum loved cooking, she didn’t work for the love of it, but because she had to. Combined with Dad’s income, Mum’s earnings kept us fed, clothed and housed. She often worked 12 hour days, on her feet the whole time, so that we could have all the things we needed, and some of the things we wanted. Whilst we never went on family holidays – and I do mean never – we always went on school camps and sporting trips and had wonderful birthdays and Christmases. I remember as an adult telling Mum in general conversation one day about how I had always wanted a proper Barbie doll but had never asked for one, because I knew the expense would be too much. She got really cross with me and said I should have told her, because she would have found a way to get me one. I told her that not having a Barbie had not done me any long term damage, to which she responded ‘well, nothing obvious’. There is no doubt at all where my dark sense of humour came from.

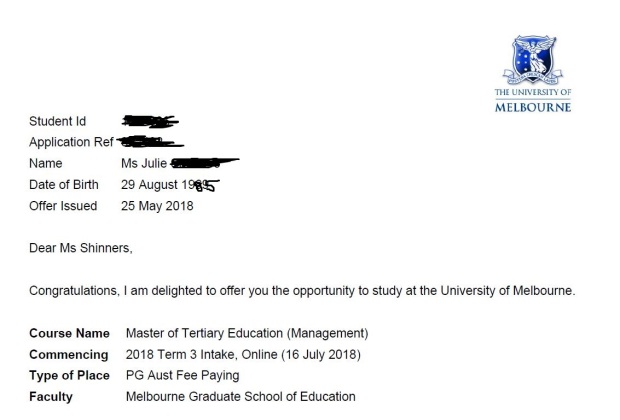

Mum was also heavily focused on the value of education, despite having only completed year 9 herself. Between us, my brother and I have three and a half University degrees (just quietly, I note that 2.5 of them are mine) which is a testament to Mum’s dedication to enabling us to have opportunities that were not available to her. We have both had successful professional careers, and this is due in no small part to Mum working her bum off to pay for us to go to university. The half of a degree is the Master’s degree I am currently undertaking at the University of Melbourne. I was just invited, on the basis of my results in that degree, to apply for a scholarship to Harvard. I so badly wanted to ring my Mum and tell her, knowing that she would have been absolutely bursting with pride at the very idea of me having a chance to study – for free – at Harvard. But I can’t ring her anymore, and that is incredibly hard. Telling Mum my good news, and my bad, had become a reflex action developed over the 50 years that I had her in my life, and at the moment I feel like I’ve had a limb removed. But knowing what I know about grief and loss, I know that it will get easier with time, although never fully go away. But the thing is, I don’t want to completely lose that feeling, I want to have a little twinge of pain at the thought of Mum, as it will remind me of how much I loved her and she loved me.

Since she died, we have had so many lovely messages from people who knew Mum, and what has resonated with me is that everyone has commented about what a kind person she was. Warm and honest, she genuinely cared about other people and what was going on in their lives. She took people at face value, and was always up for a chat. And I do mean always. Right up until the few days before she died, Mum was as sharp as a tack, and took in the small details about the people around her. She was connected to the world, and her loss has been felt at many junctures. About five months ago, Mum got new neighbours and was very excited to tell me about the Iraqi refugee family who within the first few hours of moving in had presented her with a platter of the most beautiful food. They spoke virtually no English, and Mum certainly didn’t speak Arabic or Kurmanji, but she became friends with the couple and their seven children. The four young daughters, all just commencing at the local primary school, would pop over to Mum’s most afternoons to practice their English, go over their alphabet and have her check their counting. Every time they came they would bring food, and Mum was in heaven with the delicious flat breads, stews and rice dishes. They also hosted Mum at their place, recounting with the help of photos on an iPad and Google translate, what had happened to them in Iraq, and how happy and grateful they were to be in Australia. When we told them of Mum’s death, there were tears all round and then a few hours later came over to her house, where we were starting to sort through paperwork, with a platter of food for us for lunch. When we offered them some of Mum’s plants and furniture, there were more tears, and we were repaid with help washing the outside of her house, a haircut for Hugh (the neighbour Dad was a barber in Iraq) and many other kindnesses. All without much, if any conversation, and all because my mother was a kind, loving and generous person who connected with everyone she met.

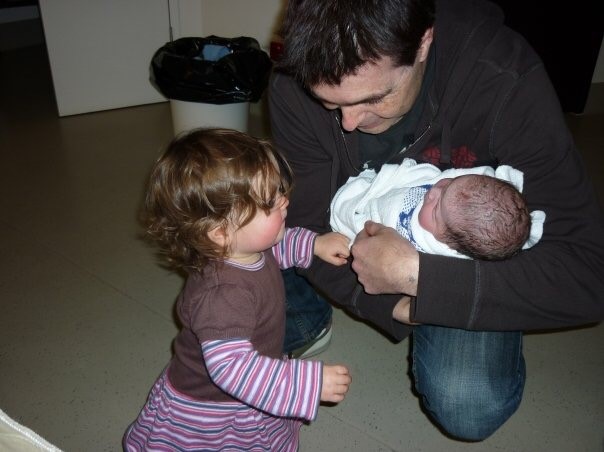

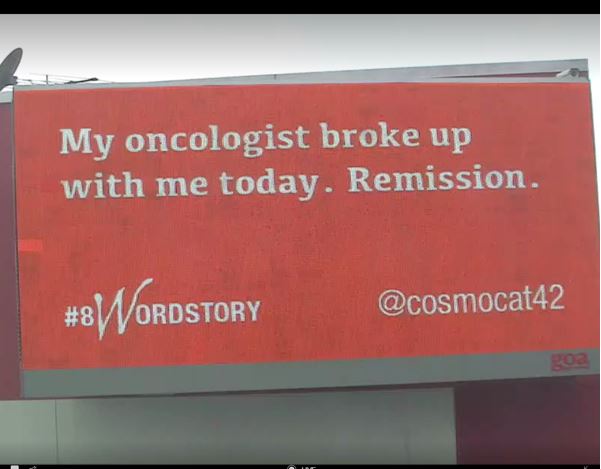

As for me, what the loss of my Mum means to me is impossible to put into words. She was there for me – always and without exception – for my whole life. I never for one second doubted her love for me, and I hope she thought the same, although admittedly the teenage years may have been a bit sketchy. When I – finally, at the age of almost 39 – had my own child, she was in seventh heaven. I can still remember the absolute joy and excitement on her face when she came to the hospital to meet Hugh for the first time. In the weeks after his birth she would come to our house every morning after Dave had gone to work, and whilst I slept she would do the washing, cook a meal, tidy up and take Hugh for a walk in the pram. When Hugh was a little bit older and I went back to work, Mum looked after him every Friday for three years, until he went to school. Mum also looked after me when I had breast cancer, and a few years later when the after-effects of chemotherapy cause me to break my shoulder, leaving me out of action for many months. During that time, Mum helped me with bathing, dressing and all of the little things like putting earrings in, as well as running the household, cooking meals and doing the washing while Dave was at work. Those were very special times for us all, and I remember my Dad commenting that Mum had a bond with Hugh unlike her connection with anyone else. Hugh is an incredibly resilient person, much like his grandmother, so his happy demeanour has remained in place for the most part. But in the quiet moments, especially at bed time, he is sad and reflective, and we talk about what she meant to us, and how hard it has been to lose her.

I always joked that if Dave and I ever divorced, my parents would choose Dave, or ‘Poor Dave’ as Mum referred to him. We’re just going to have toasted sandwiches for dinner tonight – Poor Dave will be hungry. I’ll get Dave to come and fix your dripping tap – Poor Dave will be tired. We’re having people over for dinner – Poor Dave might want a quiet night. Mum felt sorry for Dave being saddled with such an opinionated wife – despite the fact that she was the one who’d raised me that way – and so she constantly harangued me to ensure that he was being looked after. But ultimately, it was Dave who came up with the idea of how we could best look after Mum in her final years.

With the costs of maintaining and repairing her old house mounting and Mum only being on a pension, Mum decided she needed to sell up and move out, so one Sunday we took her to have a look at a few retirement villages. Mum mustered some enthusiasm – as she did for most things – but we could see how difficult it would be for her to leave her street after almost 60 years. So Dave came up with the idea that we should buy the house and renovate it for Mum. At the time I thought he was mad – Poor Dave – but it turned out to be the most amazing thing for Mum. She got a completely new home, and lived in it with her beloved dog Roy for more than two years until she went to hospital for the final time last week. I will be forever grateful that we were able to give this gift to Mum, after everything she had given to me and our family.

Having known far too many young mothers who have died, I am well aware of how privileged to have had my mother in my life for 50 years. It doesn’t make the pain of losing her any less, but it gives perspective to my pain.

I have been one of the lucky ones, to be borne of an incredibly loving and kind person who raised me to be strong, but who always had some of her own strength to spare at the times when I’d used mine all up.

She brought me into this world, and I was with her when she left, and for those two things, and everything else in between, I will be forever grateful.

Rest in peace Mum.